"The finest hotel in Bombay” now lies in a shambles

This story was originally published in Conde Nast Traveller. Cover image: Wikimedia Commons

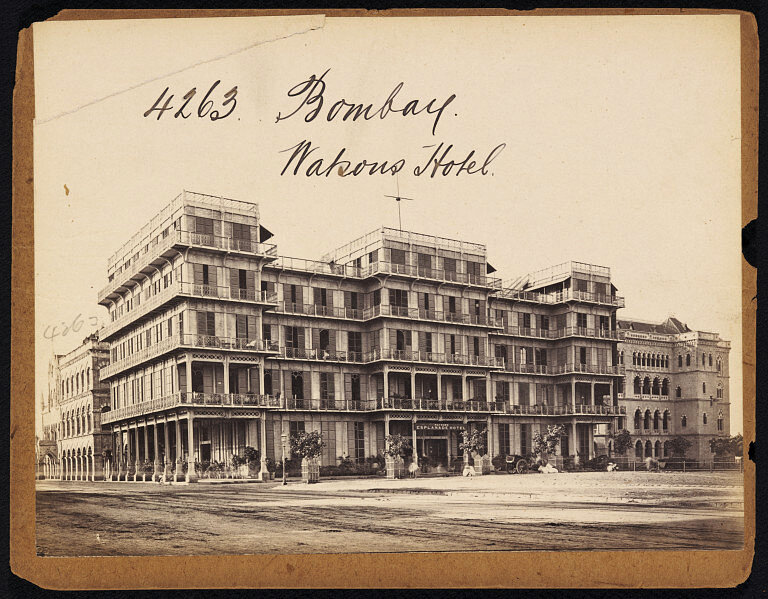

Within the bustling city of Mumbai stands the Esplanade Mansion, a quiet, forlorn, neglected structure in the Kala Ghoda precinct. Once known as Watson’s Hotel, it was one of the finest luxury hotels the country had ever seen. Owned by a successful English draper, John Watson and constructed between 1867-71, the building is a vestige of 19th century architectural proficiency. It was the first prefabricated cast-iron structure in India—and one of the few in the world. Watson, a visionary, had the building’s skeletal assembly made in England and shipped directly to Bombay.

It was within the hotel’s premises that six short films made by the Lumière Brothers were screened for the first time in the country in 1896. That was a pioneering moment in history, flagging the arrival of cinema in India. The hotel hosted the wealthy and intellectual elites, including legends like American author Mark Twain. Tragically, despite the magnitude of its historical significance, the building today is under-appreciated and is in shambles.

Designed to please

It’s hard to believe that the design for the building was rejected thrice. “It is believed that when the Ramparts Removal Committee (RRC) was looking at the plans submitted to the committee for the building, they rejected it three times. They wanted a gothic, stone structure because every other building around at the time was a Victorian gothic building,” explains conservation architect, Abha Narain Lambah. The RRC was an urban planning advisory body, which wanted to ensure that the hotel had architectural consistency to the surrounding buildings in the neighbourhood.

“Watson, however, stuck to his guns,” continues Lambah. “He kept resubmitting this design because he believed in it. Even though it might not have been visually palatable for the RRC, it was cutting-edge and was a technological marvel for that age. So, it’s a very significant building today, if you look at the history of architecture.”

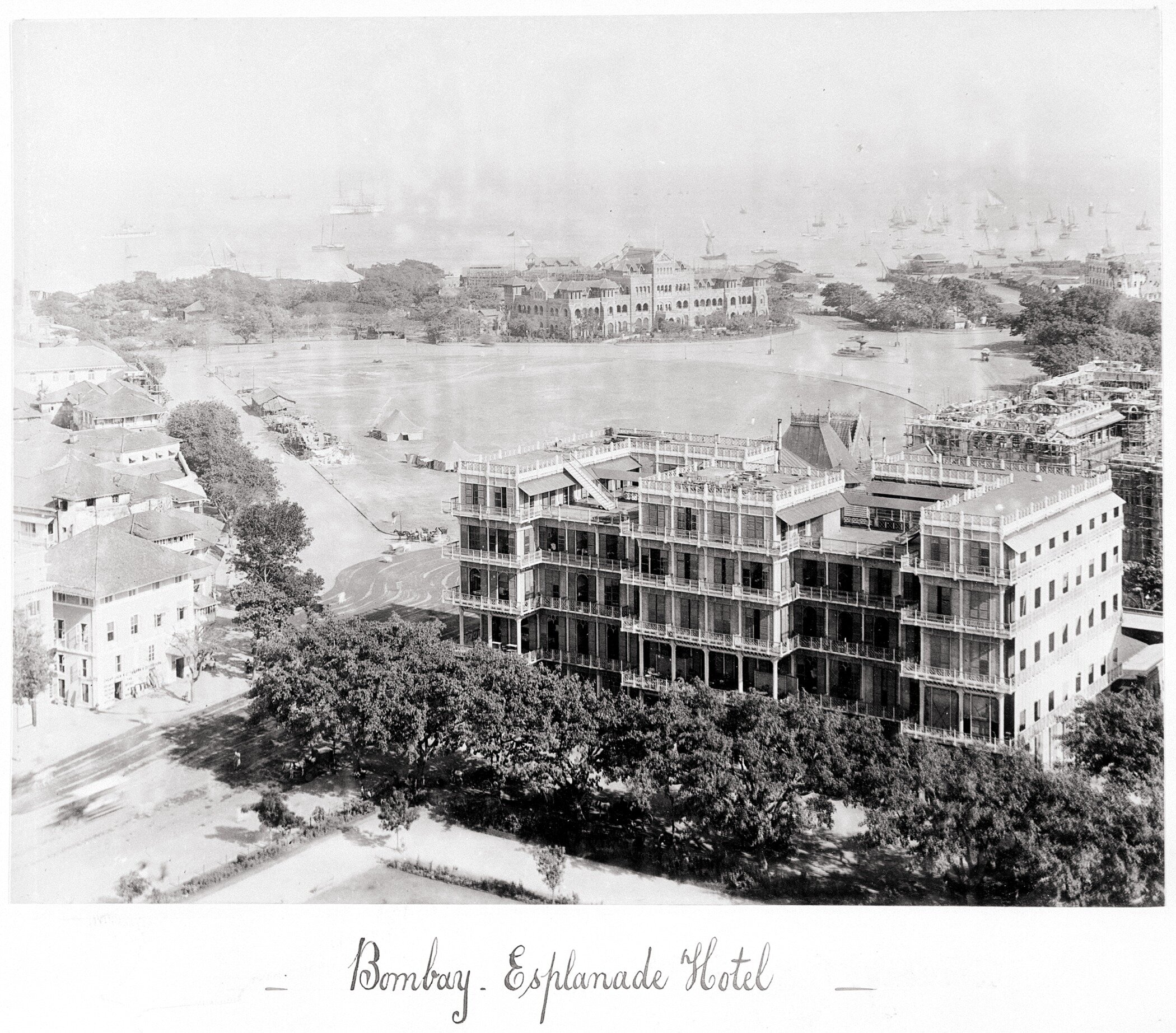

Watson’s Hotel (also called Esplanade Hotel) in late 1860s. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

‘The finest hotel in Bombay’

When the hotel opened in 1871, the Bombay Gazette (6 February 1871), declared it to be “without a doubt the finest hotel in Bombay”. It was the pinnacle of extravagance. “In those days, there were a few small hotels and taverns around in Bombay,” explains Rajan Jayakar, convener of the Greater Mumbai chapter of INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage). “But the prominent Europeans were not very comfortable staying in those accommodations. They wanted something that was more along the Western aesthetic.”

The hotel gave its guests just that. Its multi-level interiors housed a brightly-lit restaurant on the ground floor that served exquisite European cuisine, and had an attached entertainment room equipped with a pool table. In addition, it had “a first-floor dining saloon (with another attached billiard-room), and three upper storeys given over to 130 bedrooms and apartments, the uppermost of which were reserved for ‘bachelors and quasi-single gentlemen’… It commanded breath-taking views across the harbour, bays and distant hills,” notes heritage buildings historian and scholar, Johnathan Clarke in the Construction History Society journal. Almost each room boasted of an attached bathroom–a rare luxury at the time.

The grand staircase

While a central grand wooden staircase made of Burma teak connected the four floors, a swanky steam-powered elevator was available for the guests to use as well.

Image courtesy: Abha Narain Lambah.

A band of balconies wrapped around the building and each occupied room had an appointed punkah wallah—a native help employed by the hotel, who would manually operate fans. The ground-floor’s colonnaded lobby had Minton-tiled flooring, while the ornate cast iron balusters and railings featured the monogram ‘W’. The monogram is visible on the balcony’s railings even today. While a central grand wooden staircase made of Burma teak connected the four floors, a swanky steam-powered elevator (India’s first) was available for the guests to use as well. When electricity was introduced in the country in 1879, the hotel–an emblem of modernity–soon incorporated it. “By early 1890s, the [hotel] had been fitted with a hydraulic lift and electric lights and bells,” writes Clarke.

The hotel was luxurious and centrally located. “Whomsoever was a person of importance, passed through Bombay and planned to stay overnight, would prefer to stay here,” says Jayakar. “The Churchgate railway station was close by and later on, so was the Victoria Terminus. It was also situated near the docks for those who journeyed via ships. The proximity was very convenient.”

In Mark Twain’s words

In fact, when Mark Twain arrived in Mumbai after disembarking the passenger ship, S.S.Rosetta for his lecture tour in January 1896, he stayed at Watson’s Hotel. In his book, Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World, Twain describes the service provided at the establishment: “[I]n the dining-room every man’s own private native servant standing behind his chair, and dressed for a part in the Arabian Nights. Our rooms were high up, on the front. A white man—he was a burly German—went up with us, and brought three natives along to see to arranging things. About fourteen others followed in procession, with the hand-baggage; each carried an article—and only one; a bag, in some cases, in other cases less. One strong native carried my overcoat, another a parasol, another a box of cigars, another a novel, and the last man in the procession had no load but a fan. It was all done with earnestness and sincerity, there was not a smile in the procession from the head of it to the tail of it.”

The Atrium

“The central atrium was almost like a conservatory. It was covered by a glass gable roof, supported on steel truss and had Mangalore tile finishing with a few skylights.”

— Abha Lambah, conservation architect

Perhaps the most fascinating and visually arresting part of the hotel was the atrium— a big hall. “The central atrium was almost like a conservatory. It was covered by a glass gable roof, supported on steel truss and had Mangalore tile finishing with a few skylights. So, during ballroom dancing at night, it would’ve been starlit. That would’ve been quite a sight to behold in the 19th century,” imagines Lambah.

The beginning of Indian filmmaking

It is believed that it was at the atrium that the Lumière Brothers’ films were screened to a private audience in July 1896. Although the audience comprised mostly of Europeans and British people, there were a handful of well-heeled Indians in the midst, including H. S. Bhatavdekar (better known as Save Dada), who owned a photography studio. Inspired by the Lumière films, Bhatavdekar ordered a projector, camera and film reels from England, and shot his first motion picture in 1899 at Mumbai’s Hanging Gardens, documenting a wrestling game. It was the beginning of Indian filmmaking.

An urban legend

A tenacious rumour that has stuck around for decades is that Jamsetji N. Tata was once rudely turned away from the establishment’s doors, since he was a coloured man. The hotel was said to be reserved only for its colonial guests. Humiliated, Tata vowed to own a hotel far grander and majestic than the one that had rejected him. While there is no substantial evidence backing this historical anecdote, Tata did establish Taj Mahal Palace, Bombay, which opened its doors to the public in 1903. It soon became one of Watson’s Hotel’s greatest competitors.

By 1920, Watson’s Hotel’s chapter as a luxurious accommodation had concluded. The building was temporarily bought by the Maharaja of Morvi, before being purchased by the Tatas in 1944. It is said that it was used by the group as a residential quarter for its employees.

Today, the once glorious, regal structure that was considered to be the pride of Bombay, stands in ruins. In 2019, the eponymous documentary titled, Watson’s Hotel, jointly made by filmmakers Ragunath V, Nathaniel Knop and Peter Rippl, was released as a homage to the imperiled relic, featuring its occupants and their relationship to the crumbling mansion.

Watson’s Hotel, today known as Esplanade Mansion. Image courtesy: Rajan Jayakar.

The atrium, for instance, is in a despicable state. “It is currently closed by a wall at the entrance and is unfortunately used as a garbage and building material depot,” informs Ragunath. Interestingly, the same year in May 2019, the building was sealed by court order and a mammoth renovation was instructed that was estimated to cost more than Rs 50 crore. Over 150 commercial and residential tenants inhabiting the premises were directed to vacate. “No one is allowed inside the building anymore,” says Ragunath. “Before it was closed, however, there were a large number of lawyers, copy and typewriting shops, a few offices, shops in the ground level and a restaurant.”

The Esplanade Mansion is now a UNESCO World Heritage Property and has been recognised by the World Monuments Fund as one of the 100 most endangered monuments of the world. Yet, it’s unfathomable that not many are aware of the building’s inimitable legacy. The mansion that was once the pride of Bombay, a tangible heritage, is now a forgotten piece of history.